Questões de Inglês - Grammar - Linking words -

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

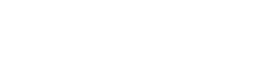

Airborne particles cause more than 3m early deaths a year

Governments are worried over traffic and other local nuisances that create filthy air. But research just published in Nature by Zhang Qiang, of Tsinghua University in Beijing, and an international team including environmental economists, physicists and disease experts, suggests the problem has a global dimension, too. Dr Zhang’s analysis estimates that in 2007 — the first year for which complete industrial, epidemiological and trade data were available when the team started work — more than 3m premature deaths around the world were caused by emissions of fine particulate matter (known as PM2.5, because the particles in question are less than 2.5 microns across).

Of these, the team reckon just under an eighth were associated with pollutants released in a part of the world different from that in which the death occurred, thanks to transport of such particles from place to place by the wind. Almost twice as many (22% of the total) were a consequence of goods and services that were produced in one region (often poor) and then exported for consumption in another (often rich, and with more meticulous environmental standards for its own manufacturers).

In effect, such rich countries are exporting air pollution, and its associated deaths, as they import goods. As far as China is concerned, that phenomenon is probably abating. Chinese coal consumption has been on the wane since 2013, so premature deaths there from toxic air are now probably dropping. But other industrialising countries, such as India, may yet see an increase.

(www.economist.com, 01.04.2017. Adaptado.)

No trecho do terceiro parágrafo “so premature deaths there from toxic air are now probably dropping”, o termo sublinhado equivale, em português, a

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

What Does It Mean to Tear Down a Statue?

Protesters throwing the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston into a harbour.

Statues of historical figures, including slave traders and Christopher Columbus, are being toppled throughout the U.S. and around the world. This follows years of debate about public display of Confederate symbols. We interviewed the art historian Erin L. Thompson about the topic. Read the excerpt from the interview.

Q. What are some of the issues that arise when we talk about statues being torn down?

A. We have as humans been making monuments to glorify people and ideas since we started making art, and since we started making statues, other people have torn them down. So it’s not surprising that we are seeing people rebelling against ideas that are represented by these statues today.

Q. What do the recent attacks on statues tell us about the protests themselves?

A. The current attacks on statues are a sign that what’s in question is not just our future but our past, as a nation, as a society. These attacks show that we need to question the way we understand the world, even the past, in order to get to a better future.

Q. What’s a statue?

A. I think a statue is a bid for immortality. It’s a way of solidifying an idea and making it present to other people. It’s not the statues themselves but the point of view that they represent. And these [the ones being destroyed] are statues in public places, right? So these are statues claiming that this version of history is the public version of history.

Also, many Confederate statues are made out of bronze, a metal that you can melt down. The ancient Greeks made their major monuments out of bronze. Hardly any of these survived because as soon as regimes changed, as soon as there was war, it got melted down and made into money or a statue of somebody else.

We have been in a period of peace and prosperity — not peace for everybody, but the U.S. hasn’t been invaded, we’ve had enough money to maintain statues. So our generation thinks of public art as something that will always be around. But this is a very ahistorical point of view. I wish that what is happening now with statues being torn down didn’t have to happen this way. But there have been peaceful protests against many of these statues which have come to nothing. So if people lose hope in the possibility of a peaceful resolution, they’re going to find other means.

(www.nytimes.com, 11.06.2020. Adaptado.)

O trecho “the point of view that they represent”, no contexto da resposta à terceira pergunta, pode corresponder, em português, a:

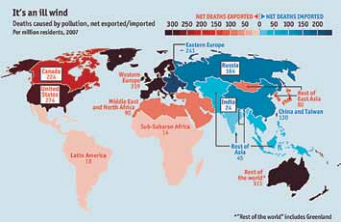

Leia a tirinha para responder à questão

No trecho do segundo quadrinho “the vision in your right eye is dim so the doctor has patched the left one”, o termo sublinhado pode ser substituído, sem alteração de sentido, por

TEXT

The end of life on Earth?

It weighted about 10,000 tons, entered the

atmosphere at a speed of 64,000 km/h and exploded

over a city with a blast of 500 kilotons. But on 15

February 2013, we were lucky. The metereorite that

[05] showered pieces of rock over Chelyabinsk, Russia, was

relatively small, at only about 17 metres wide. Although

many people were injured by falling glass, the damage

was nothing compared to what had happened in Siberia

nearly one hundred years ago, when a relatively small

[10] object (approximately 50 metres in diameter) exploded in

mid-air over a forest region, flattening about 80 million

trees. If it had exploded over a city such as Moscow or

London, millions of people would have been killed.

By a strange coincidence, the same day that the

[15] meteorite terrified the people of Chelyabinsk, another

50m-wide asteroid passed relatively close to Earth.

Scientists were expecting that visit and know that the

asteroid will return to fly close by us in 2046, but the

Russian meteorite earlier in the day had been too small

[20] for anyone to spot.

Most scientists agree that comets and asteroids

pose the biggest natural threat to human existence. It

was probably a large asteroid or comet colliding with

Earth which wiped out the dinosaurs about 65 million

[25] years ago. An enormous object, 10 to 16 km in diameter,

struck the Yucatan region in Mexico with the force of 100

megatons. That is the equivalent of one Hiroshima bomb

for every person alive on Earth today.

Many scientists, including the late Stephen

[30] Hawking, say that any comet or asteroid greater than

20km in diameter that hits Earth will result in the

complete destruction of complex life, including all

animals and most plants. As we have seen even a much

smaller asteroid can cause great damage.

[35] The Earth has been kept fairly safe for the last 65

million years by good fortune and the massive

gravitational field of the planet Jupiter. Our cosmic

guardian, with its stable circular orbit far from the sun,

sweeps up and scatters away most of the dangerous

[40] comets and asteroids which might cross Earth’s orbit.

After the Chelyabinsk meteorite, scientists are now

monitoring potential hazards even more carefully but, as

far as they know, there is no danger in the foreseeable

future.

[45] Types of space rocks

• Comet – a ball of rock and ice that sends out a

tail of gas and dust behind it. Bright comets only appear

in our visible night sky about once every ten years.

• Asteroid – a rock a few feet to several kms in

[50] diameter. Unlike comets, asteroids have no tail. Most

are to small to cause any damage and burn up in the

atmosphere.

• Meteoroid – part of an asteroid or comet.

• Meteorite – what a meteoroid is called when it

[55] hits Earth.

Taken from: http://learningenglishteens.britishcouncil.org - Access on 29/06/2020

In “scientists were expecting that visit” (line 17), the underlined word has the same use as in

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Switzerland’s mysterious fourth language

Despite Romansh being one of Switzerland’s four national languages, less than 0.5% percent of Swiss can answer that question – “Do you speak Romansh?” – with a “yes”. Romansh is a Romance language indigenous to Switzerland’s largest canton, Graubünden, located in the south-eastern corner of the country. In the last one hundred years, the number of Romansh speakers has fallen 50% to a meagre 60,000. Travellers in the canton can still see Romansh on street signs, or hear it in restaurants when they’re greeted with “Allegra!” (Welcome in). But nearly 40% of Romansh speakers have left the area for better job opportunities and it’s rare that you will see or hear Romansh outside the canton. In such a small country, can a language spoken by just a sliver of the population survive, or is it as doomed as the dinosaur and dodo?

Language exists to convey a people’s culture to the next generation, so it makes sense that the Swiss are protective of Romansh. When the world loses a language, as it does every two weeks, we collectively lose the knowledge from past generations. “Language is a salient and important expression of cultural identity, and without language you will lose many aspects of the culture,” said Dr Gregory Anderson, Director of the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages.

Without the Romansh language, who is to say if customs like Chalandamarz, an ancient festival held each 1 March to celebrate the end of winter and coming of spring, will endure; or if traditional local recipes like capuns – spätzle wrapped in greens – will be forgotten? “Romansh contributes in its own way to a multilingual Switzerland,” says Daniel Telli, head of the Unit Lingua. “And on a different level, the death of a language implies the loss of a unique way to see and describe the world.”

(Dena Roché. www.bbc.com, 28.06.2018. Adaptado.)

In the fragment from the second paragraph “Language exists to convey a people’s culture to the next generation, so it makes sense that the Swiss are protective of Romansh.”, the term underlined introduces

Instrução: A questão está relacionada ao texto abaixo.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and

Sciences has announced a new category in

time for next February’s awards ceremony:

“achievement in popular film”. The idea is

[5] that, alongside the time-honoured “Best

Picture” category, there will be another for

films which have a broader appeal:

blockbusters, in other words. Ironically, the

announcement has been anything but

[10] popular. On social media, responses to this

idea have ranged from hostile to very hostile

indeed. Many feel that the once-prestigious

Oscars are dumbing down to the level of the

MTV Awards. What’s next—Best kiss? Loudest

[15] shoot-out? Most skyscrapers flattened by

aliens in a single action sequence?

The concept of the “Hit Oscar” or the

“Popcorn Oscar”, as it has been nicknamed,

raises other questions, too. To start with, who

[20] decides whether or not a film is popular?

What are the criteria or thresholds? And isn’t

it an insult to nominees, the implicit

suggestion being that hit films can’t be artistic

(and vice versa)?

[25] The timing, too, is off. “Black Panther”,

Marvel’s Afrofuturist superhero blockbuster,

could well have been nominated for best

picture in 2019. Indeed, it could well have

won, ……… acknowledging the superhero

[30] boom as well as emphasising just how

successful films with black casts and creative

teams can be. But it is now likely that “Black

Panther” will be shoved into the “popular”

ghetto, and that the best-picture prize will go

[35] to an indie drama. If so, the introduction of a

new category will have helped maintain the

status quo, rather than upending it.

It is understandable that the Oscars’

organisers should want to shake up the

[40] ceremony’s format, bearing in mind how low

its television ratings have fallen. One reason

for this decline, the theory goes, is that best-

picture winners are no longer the films that

the great American public is queuing up to

[45] see.

But if hugely profitable, crowd-pleasing films

aren’t winning best picture these days, it is

not because the Academy’s voters are

becoming more snobbish or sophisticated in

[50] their tastes. It is because Hollywood has

stopped making middlebrow historical epics

that used to be a shoo-in. What the

introduction of the popular category

acknowledges is that there are now hardly

[55] any studio films in the chasm between shiny

comic-book movies and quirky indie

experiments. The industry is producing

nothing for grown-up viewers who want more

scale and spectacle than they can get from a

[60] low-key drama, but who don’t fancy seeing

people in colourful costumes firing laser

beams at each other.

The new division between best picture and

popular picture may be ill-judged, but it

[65] reflects a pre-existing dichotomy between

arthouse and multiplex fare. So have pity on

the poor Academy. If Hollywood studios

weren’t quite so obsessed with superhero

franchises, the Oscars might not be in this

[70] mess in the first place.

Adaptado de: https://www.economist.com/prospero/2018/08 /11/the-academy-announces-a-misguided-newcategory. Acesso em: 08 ago. 2018.

Assinale a alternativa que preenche adequadamente a lacuna da linha 29.

Faça seu login GRÁTIS

Minhas Estatísticas Completas

Estude o conteúdo com a Duda

Estude com a Duda

Selecione um conteúdo para aprender mais:

Artistas, autores e suas obras

Consequências políticas e sociais

Declaração dos Direitos do Homem e do Cidadão

Definição e classificação de cilindro

Definição e classificação de cone

Definição e classificação de pirâmide

Definição e elementos da esfera

Energia potencial gravitacional

Geometria Molecular e Polaridade

João Baptista Figueiredo (79-85)

Luiz Inácio (Lula) - 2002-2010

Polígonos inscritos e circunscritos na circunferência

Descolonização da África e Ásia

Deslocamento de Espelhos Planos

Determinação cromossômica do sexo

Dinâmica do Movimento Circular

Ditongos abertos "éi", "ói", "éu"

Elemento, substância, mistura e alotropia

Elementos cênicos e coreográficos

Empregos do hífen com prefixos

Entropia e energia livre de Gibbs

Equacionamento e balanceamento de reações

Equipamentos, materiais e vidrarias

Escola de Frankfurt / Indústria cultural

Estados físicos e mudanças de estado

Família Real Portuguesa no Brasil

Fontes de energia e recursos naturais

Formas de excreção nos animais

Função definida por mais de uma sentença

Função polinomial do primeiro grau

Função polinomial do segundo grau

Funções Trigonométricas Inversas

Future perfect continuous / progressive

Governos Militares (1964-1985)

Herança ligada aos cromossomos sexuais

Ideias sociais e políticas do século XIX

Independência da América Latina

Isótopos, isótonos, isóbaros e isoeletrônicos

Lei da Gravitação Universal (Newton)

Lei das Proporções Definidas (Prost)

Lei das Proporções Múltiplas (Dalton)

Leis da Conservação das Massas (Lavoisier)

Localização e movimentação no espaço

Materiais homogêneos e heterogêneos

Matrizes estéticas e culturais

Modelos de poder: Populismo, Coronelismo e outros

Modelos de Produção Capitalista

Movimento Circular Uniformemente Variado

Movimento Uniformemente Variado

Mutações Cromossômicas Estruturais

Mutações Cromossômicas Numéricas

Número de oxidação e oxirredução

O e U / E e I em final de palavras

Orações subordinadas adjetivas

Orações subordinadas adverbiais

Orações subordinadas substantivas

Organização (família, grupos etc.)

Outras funções polinomiais (>2)

Palavras homônimas e parônimas

Palavras terminadas em ÃO e à / ÃO e AM

Palavras terminadas em ÊS, ESA, EZ, EZA

Palavras terminadas em OSO, OSA

Palavras terminadas em SSE / ICE

Past perfect continuous / progressive

Perímetro de figuras planas e superfícies

Planejamento, execução e análise de ações

Polaridade e eletronegatividade

Present continuous / progressive

Present continuous / progressive with future meaning

Present perfect continuous / progressive

Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo

Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo

Pretérito perfecto de indicativo

Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo

Primeira República (1889-1930)

Projeção cilíndrica e projeção cônica

Propriedades periódicas e aperiódicas

Qualidades Fisiológicas do Som

Queda da União Soviética e formação da Rússia

Queda Livre e Lançamento Vertical

Questão Indígena, Racial e de Gênero

Redes de transporte e de comunicação

Reformas religiosas e Contrarreforma

Relações métricas em triângulos

Relações métricas no triângulo retângulo

Relações trigonométricas no triângulo retângulo

República Democrática (1945-1964)

Retículo Endoplasmático Granuloso/ Não Granuloso

Revolução Americana (Independência)

Revolução Industrial (1ª Fase)

Revolução Industrial (2ª Fase)

Seleção Natural: casos de resistência

Sistemas excretores nos animais

Sólidos inscritos e circunscritos

Temperaturas de fusão e ebulição

Tendências da arte contemporânea

Teorema da decomposição em fatores

Teorema fundamental da Álgebra

Teoria sintética da evolução (Neodarwinismo)

Terminações "-são", "-ção" e "-ssão"

texto de divulgação científica

The genitive (?s) ? possessive case

Transformações - Termodinâmica (gráficos)

Transformações dos Gases (gráficos)

Transformações trigonométricas

Unidades de medida não padronizadas

Unidades de medida não padronizadas

Unidades de medida não padronizadas

Unidades de medida não padronizadas

Unidades de medida padronizadas

Unidades de medida padronizadas

Unidades de medida padronizadas

Unidades de medida padronizadas

Unidades de medida padronizadas

Usos de "por que", " por quê", "porque" e "porquê"

Verbos terminados em "-uir" e em "-uar"

Verso, rima, métrica, sonoridade, estrofação