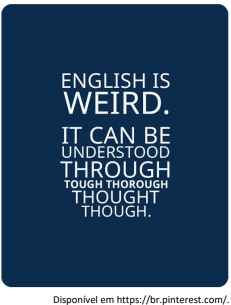

Questões de Inglês - Vocabulary - Word formation

Em relação à compreensão do idioma inglês, o texto ilustra

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Switzerland’s mysterious fourth language

Despite Romansh being one of Switzerland’s four national languages, less than 0.5% percent of Swiss can answer that question – “Do you speak Romansh?” – with a “yes”. Romansh is a Romance language indigenous to Switzerland’s largest canton, Graubünden, located in the south-eastern corner of the country. In the last one hundred years, the number of Romansh speakers has fallen 50% to a meagre 60,000. Travellers in the canton can still see Romansh on street signs, or hear it in restaurants when they’re greeted with “Allegra!” (Welcome in). But nearly 40% of Romansh speakers have left the area for better job opportunities and it’s rare that you will see or hear Romansh outside the canton. In such a small country, can a language spoken by just a sliver of the population survive, or is it as doomed as the dinosaur and dodo?

Language exists to convey a people’s culture to the next generation, so it makes sense that the Swiss are protective of Romansh. When the world loses a language, as it does every two weeks, we collectively lose the knowledge from past generations. “Language is a salient and important expression of cultural identity, and without language you will lose many aspects of the culture,” said Dr Gregory Anderson, Director of the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages.

Without the Romansh language, who is to say if customs like Chalandamarz, an ancient festival held each 1 March to celebrate the end of winter and coming of spring, will endure; or if traditional local recipes like capuns – spätzle wrapped in greens – will be forgotten? “Romansh contributes in its own way to a multilingual Switzerland,” says Daniel Telli, head of the Unit Lingua. “And on a different level, the death of a language implies the loss of a unique way to see and describe the world.”

(Dena Roché. www.bbc.com, 28.06.2018. Adaptado.)

No trecho do primeiro parágrafo “nearly 40% of Romansh speakers”, a palavra sublinhada pode ser substituída, sem alteração de sentido, por

Let´s Talk About Diversity

Greg Parks

In the midst of significant global changes such as generational turnover, talent shortage and advancing technology, Greg Parkes, Executive General Manager at Autopia, shares the organisation’s journey towards a more diverse and inclusive workplace.

There are thousands of articles discussing the importance of diversity, while study after study proves the economic benefits of a diverse workforce to an organisation. As a result, over the last decade, the corporate world has focused more on diversity, celebrating our differences in gender, cultural background, ways of thinking and more.

The journey towards diversity

At Autopia, the importance of diversity and inclusion stems from the core of our business: our customers. Having built an organisation with a personalised, highly consultative approach, it was evident to us that our customers came from a whole range of backgrounds, and our staff should too. So, in an effort to learn how to promote diversity and inclusion within our organisation and create a positive impact in our business community, we embarked on our own diversity and inclusion journey, leading to the development of our thought leadership program.

Diversity matters: facilitating the conversation

Through Autopia’s Diversity and Inclusion thought leadership program, we have had the privilege of sharing experiences with corporate leaders from around Australia, and partnered with pivotal organisations, including UN Women National Committee of Australia and Juggle Strategies, a workplace flexibility consultancy firm. Through these partnerships, we have developed a series of White Papers for business, exploring gender and cultural diversity, as well as workplace flexibility, and best practices for promoting and implementing effective diversity and inclusion programs within a business. With the objective of generating discussion around these issues, these White Papers also aim to provide guidance for companies on their own journey of change. Along the way, and thanks to insights from our expert partners, we have learned that it is not enough to achieve a statistically diverse workforce; true inclusion comes when there is a cultural shift within the organisation. As Vernā Myers, Author and Diversity Advocate once said, “Diversity is being invited to the party; inclusion is being asked to dance.”

Undoubtedly, changing an organisation’s culture can be slow. In fact, achieving diversity and inclusion is not a one-off, set-and-forget exercise. It is an ever-evolving process that must go beyond written procedures to become part of the day-to-day life of an organisation. Achieving diversity and inclusion is a process that requires us to re-think how we do business, but one that we know can have a positive and tangible effect on productivity and performance. Working towards diversity and inclusion in the workplace is not only the right thing to do; it’s the smart thing to do.

(Fonte:http://www.hcamag.com/opinion/opinion-lets-talk-aboutdiversity-241797.aspx)

Undoubtedly é composta pelo uso de afixos. A palavra que passa pelo mesmo processo de formação de palavras é

TEXTO

Can eating meat be eco-friendly?

Every year we raise and eat 65 billion animals, that’s nine animals for every person on the globe, and it’s having a major impact on our planet.

(...)

I like eating meat but I know that my food preferences, and those of a few billion fellow carnivores, comes at a cost. Nearly a third of the Earth’s ice-free land surface is already devoted to raising the animals we either eat or milk. Roughly 30% of the crops we grow are fed to animals. The latest UN Food and Agriculture Organisation reports suggest livestock are responsible for 14.5% of man-made greenhouse gas emissions - the same amount produced by all the world’s cars, planes, boats and trains.

(...)

The problem lies in what the cows eat. Unlike most mammals, cattle can live on a diet of grass, thanks to the trillions of microbes that live in their many stomachs. These microbes break down the cellulose in grass into smaller, nutritious molecules that the cows digest, but while doing so the microbes also produce huge amounts of explosive methane gas which the cows burp out.

Fonte: http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-28858289. Acesso em 27/08/2014. Adaptado.

O sufixo –er na palavra smaller (último parágrafo) tem a mesma função morfológica que o sufixo –er em qual das seguintes palavras?

Ebooks don’t spell the end of literature

E-readers pose no threat to books — quite the opposite, they may just re-kindle a generation’s love for the written word

The other day I was on a train, reading a book. The young woman seated next to me was also reading a book. We were both enjoying classics of English literature — hers was a Charlotte Brontë novel. The only difference was that my book was made of paper, and hers of light on the screen of an e-reader.

Books are changing; but are the fundamentals of reading and writing? Seeing a reader gripped by digital Brontë made me aware that electronic books are giving literacy a new dimension. Many people like this new way of enjoying a book, and some may prefer it. Look at it this way: since the 1960s when transistor radios and — by the end of the decade — colour televisions transformed popular culture, every new technological advance has strengthened the appeal of the sort of media that rivals the book. Music and film, TV and video games: all have outshone books in technological glamour. Now, suddenly, here is a technological way to read a book. It’s kind of cool.

I don’t believe this technology will destroy the printed object; real books will never lose their charm. But people who see today’s new ways of reading as a threat are fantasising. Literacy has been under attack for decades, from all directions. Reading suffered its worst assault, perhaps, from television. My grandmother used to read all the time — in fact she was the village librarian — but you wouldn’t find many people in that same village today with the TV off, their heads in books. It is therefore surely arguable that e-readers are not the destroyers but the saviours of the book. A generation may return to the written word because of this technology.

Internet: <http://www.theguardian.com> (adapted).

Based on the text above, judge the item.

In the excerpt “Music and film, TV and video games: all have outshone books in technological glamour.”, the main verb contains a prefix.

Text

The Festival of Lights (Divali) in Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago Hindu festivals, customs and traditions form an integral part of society and “Divali” is no exception. A large percentage of the population consists of ethnic Indians and many are Hindus. The celebration of “Divali” in Trinidad and Tobago is a national holiday with a significant amount of functions to celebrate the occasion. Recently the celebration has not only been extended to the homes and communities but organizations have also embraced this festival with special events held to commemorate it. This is evident in banks, schools and other organizations where members of staff organize “Divali” cultural programmes, dress in Indian ethnic wear and distribute sweets to their staff and customers.

One of the highpoints of the celebrations is held at the Divali Nagar site which is the official headquarters of the National Council of Indian Culture. At the Nagar there is a week of cultural, religious, educational and commercial activities which attract a wide cross section of the population including members of government, diplomatic agencies and parliamentarians.

Hindus in Trinidad and Tobago are also involved in cleaning and redecorating their homes for this auspicious occasion. They also maintain a period of abstinence or fasting. The day of “Divali” is marked with a host of activities in the homes where various dishes and sweets are prepared and “Pooja” is performed. Family members participate in evening worship at 6 o’clock to Mother Lakshmi, the Goddess of prosperity and wealth. They then light their homes with several dozens of “deyas” and distribute delicacies to their families, friends and the community. This sacred festival is known to bring about positive feelings to the community such as a sense of unity, cleanliness, harmony and festivity.

Internet: www2.nalis.gov.tt (adapted).

Based on the text, judge the item below.

In the last sentence of the text, “bring about” conveys the opposite idea of inhibit.

Faça seu login GRÁTIS

Minhas Estatísticas Completas

Estude o conteúdo com a Duda

Estude com a Duda

Selecione um conteúdo para aprender mais: