Questões de Inglês - Vocabulary - Arts and Entertainment

Brazilian protest songs: “Peace without a voice is no peace but fear”

I was born a year after the military coup in Brazil. The dictatorship that followed lasted from

1964 until 1985 - all my childhood and teenage years. But until I was 13 or 14 years old, I had

no clue of what was going on in my country. I lived in a small town and my parents were not

involved in politics. We listened to the radio, watched the news on TV and had a subscription to

[5] a national newspaper, but all the media were completely censored at that time. The fact that the

newspaper was sometimes printed with a blank space or a cake recipe in the middle of the news

never really caught my attention. It was always like that and I didn’t know any better.

I had my first glimpse of what it really meant to have a military government and what kind

of things were going on through songs. There was a song that I liked a lot, O bêbado e a

[10] equilibrista, although the lyrics didn’t make much sense to me: “My Brazil… / that dreams of the

return / of Henfil’s brother / and so many people that left / on rocket fins”. Henfil was a famous

cartoonist, but who was his brother? Who were the people who left? What were they singing

about? This was in 1979 and I was 13.

Thanks to this song by João Bosco and Aldir Blanc (sung by Elis Regina) and the questions I

[15] started to ask, I heard for the first time about all the artists, journalists and activists that had

been persecuted, imprisoned, tortured and exiled. Many had disappeared or been killed by the

military regime. This song became an anthem for the amnesty of political prisoners and activists

in exile, which was announced later in that same year.

In fact, due to the extreme censorship during the period of military dictatorship in Brazil, songs

[20] were one of the few ways to send political messages. Despite the tight surveillance of the censors,

they flourished, giving a voice to the resistance movement. Like Para não dizer que não falei das

flores, by Geraldo Vandré, which was interpreted as a call for armed struggle.

Words and phrases with double meanings were used to escape censorship and persecution. The

greatest master in this art was Chico Buarque de Holanda. His clever lyrics were often approved

[25] by the censors, who would only later realise what the songs were really about. But then, of

course, it was too late. That was the case with Apesar de você, which was censored only after it

had already become an anthem on the streets. At first sight, it appears to be a samba about a

lover’s quarrel. Actually, it was a sharp critique of the authoritarian regime and an act of direct

defiance aimed at the dictators.

[30] With the advent of democracy and the new freedom of expression in the late 1980s, protest

songs played less of a role in Brazil for a while, but in the 1990s they once again became a

powerful channel to voice social discontent. One of bands active in this period was O Rappa, with

the song A paz que eu não quero. The fight against social inequality, urban and police violence

and racial discrimination are the most common themes. Nowadays, the lyrics are explicit and the

messages are clear.

Mariângela Guimarães rnw.nl

The context often helps if one needs to guess the meaning of an unknown word. For example, the word lyrics appears in three sentences from the text:

although the lyrics didn’t make much sense to me: (l. 10)

His clever lyrics were often approved by the censors, (l. 24-25)

Nowadays, the lyrics are explicit (l. 34)

Based on these examples, lyrics is translated as:

A questão se refere ao texto a seguir:

[…] A picture of Brighton beach in 1976, featured in the Guardian a few weeks ago, appeared to show an alien

race. Almost everyone was slim. I mentioned it on social media, then went on holiday. When I returned, I found that

people were still debating it. The heated discussion prompted me to read more. How have we grown so fat, so fast? To

my astonishment, almost every explanation proposed in the thread turned out to be untrue. […] The obvious

[5] explanation, many on social media insisted, is that we’re eating more. […]

So here’s the first big surprise: we ate more in 1976. According to government figures, we currently consume an

average of 2,130 kilocalories a day, a figure that appears to include sweets and alcohol. But in 1976, we consumed

2,280 kcal excluding alcohol and sweets, or 2,590 kcal when they’re included. I have found no reason to disbelieve the

figu res. […]

[10] So what has happened? The light begins to dawn when you look at the nutrition figures in more detail. Yes, we

ate more in 1976, but differently. Today, we buy half as much fresh milk per person, but five times more yoghurt, three

times more ice cream and – wait for it – 39 times as many dairy desserts. We buy half as many eggs as in 1976, but a

third more breakfast cereals and twice the cereal snacks; half the total potatoes, but three times the crisps. While our

direct purchases of sugar have sharply declined, the sugar we consume in drinks and confectionery is likely to have

[15] rocketed (there are purchase numbers only from 1992, at which point they were rising rapidly. Perhaps, as we

consumed just 9kcal a day in the form of drinks in 1976, no one thought the numbers were worth collecting.) In other

words, the opportunities to load our food with sugar have boomed. As some experts have long proposed, this seems to

be the issue.

The shift has not happened by accident. As Jacques Peretti argued in his film The Men Who Made Us Fat, food

[20] companies have invested heavily in designing products that use sugar to bypass our natural appetite control

mechanisms, and in packaging and promoting these products to break down what remains of our defenses, including

through the use of subliminal scents. They employ an army of food scientists and psychologists to trick us into eating

more than we need, while their advertisers use the latest findings in neuroscience to overcome our resistance.

They hire biddable scientists and thinktanks to confuse us about the causes of obesity. Above all, just as the

[30] tobacco companies did with smoking, they promote the idea that weight is a question of “personal responsibility”. After

spending billions on overriding our willpower, they blame us for failing to exercise it.

To judge by the debate the 1976 photograph triggered, it works. “There are no excuses. Take responsibility for

your own lives, people!” “No one force feeds you junk food, it’s personal choice. We’re not lemmings.” “Sometimes I think

having free healthcare is a mistake. It’s everyone’s right to be lazy and fat because there is a sense of entitlement about

[35] getting fixed.” The thrill of disapproval chimes disastrously with industry propaganda. We delight in blaming the victims.

More alarmingly, according to a paper in the Lancet, more than 90% of policymakers believe that “personal

motivation” is “a strong or very strong influence on the rise of obesity”. Such people propose no mechanism by which the

61% of English people who are overweight or obese have lost their willpower. But this improbable explanation seems

immune to evidence.

[40] Perhaps this is because obesophobia is often a fatly-disguised form of snobbery. In most rich nations, obesity

rates are much higher at the bottom of the socioeconomic scale. They correlate strongly with inequality, which helps to

explain why the UK’s incidence is greater than in most European and OECD nations. The scientific literature shows how

the lower spending power, stress, anxiety and depression associated with low social status makes people more

vulnerable to bad diets.

[45] Just as jobless people are blamed for structural unemployment, and indebted people are blamed for impossible

housing costs, fat people are blamed for a societal problem. But yes, willpower needs to be exercised – by governments.

Yes, we need personal responsibility – on the part of policymakers. And yes, control needs to be exerted – over those

who have discovered our weaknesses and ruthlessly exploit them.

Adaptado de:

Assinale a alternativa que pode substituir ‘as’ na sentença “As Jacques Peretti argued in his film The Men Who Made Us Fat, food companies have invested heavily in designing products [...]” (linhas 19-20) mantendo o mesmo sentido do texto e a correção gramatical.

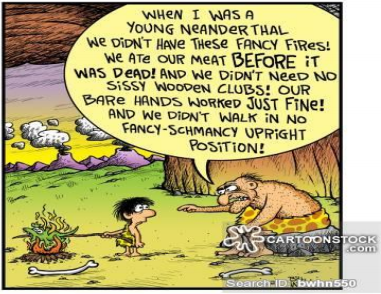

Read the comic and answer question

In the comic, the grandfather is

TEXTO II

"Firefighters shouting slogans during a public servants’ demonstration against austerity measures in Rio de Janeiro in December.” (CreditYasuyoshi Chiba/Agence France- Presse — Getty Images)

Brazil’s Leaders Tout Austerity

Brazil’s sickly economy is hemorrhaging thousands of jobs a day, States are scrambling to pay police officers and teachers, and money for subsidized meals is in such short supply that one legislator suggested that the poor could “eat every other day.” Still, not everyone is suffering. Civil servants in the judicial branch are enjoying a 41 percent raise. Legislators here in São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city, voted to increase their own salaries by more than 26 percent. And Congress, which is preparing to cut pension benefits around the country, is now allowing its members to retire with lifelong pensions after just two years in office.

Brazil is struggling to pull out of its worst economic crisis in decades, and President Michel Temer says the country needs to curb public spending to do so. Yet, it did not help his dismal approval ratings when he hosted a lavish taxpayerfunded banquet to persuade members of Congress to support his budget cuts, with 300 guests eating shrimp and filet mignon. Outside such rarefied circles, Mr. Temer’s austerity measures are igniting a fierce debate over how the richest and most powerful Brazilians are protecting their wealth and privileges at a time when much of the country is enduring a harrowing economic decline.

economic decline.

“This government talks about austerity for everyone, but of course forces the costs on society’s most vulnerable people,” said Giovana Santos Pereira, 25, a schoolteacher. “It’s ridiculous to the point of being tragic.” Much of the ire revolves around the centerpiece of Mr. Temer’s austerity drive: his success in persuading the scandal-ridden Congress to impose a cap on federal spending for the next 20 years.

Mr. Temer, who rose to power last year after supporting the impeachment of his predecessor, Dilma Rousseff, says the cap, which would limit the growth in spending to the rate of inflation, is needed to scale back ballooning budget deficits. Investors have applauded the measure as a turning point for Latin America’s largest economy. But critics are lashing out at the spending cap, saying it could harm the poor for decades to come, especially in areas like education. Philip Alston, the United Nations special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, said the spending cap placed Brazil “in a socially retrogressive category all of its own.”

The debate is all the more caustic because Mr. Temer’s government is resisting calls to raise taxes on wealthy Brazilians, who still enjoy what some economists describe as one of the most generous tax systems for the rich among major economies. For instance, Brazilians remain exempt from paying any taxes at all on dividends from stock holdings, and they can easily use loopholes to significantly lower taxes on other sources of income.

Economists at the government’s Institute of Applied

Economic Research said in a 2016 study that a 15 percent tax on dividends could generate nearly $17 billion in revenue a year, but such proposals have failed to gain traction in a government that has shifted to the right. “The system is engineered to perpetuate inequality, and Temer is doubling down on bets that Brazil needs Greek-style austerity,” said Pedro Paulo Zahluth Bastos, an economist at the Universidade de Campinas, drawing parallels between Brazil’s multiyear slowdown and Greece’s seemingly interminable economic crisis.

Mr. Temer has not been a popular president, and his approval ratings stand at just 10 percent. But his supporters point out that his leftist predecessor, Ms. Rousseff, sought her own austerity measures before her ouster last year, and that his government has promised to maintain some widely popular antipoverty programs expanded by her party years ago.

Mr. Temer’s government says it is reversing the freespending ways of previous governments. Brazil’s economy shrank about 4 percent in 2016, when its political class was consumed by infighting over the impeachment. But last month, the finance minister, Henrique Meirelles claimed, “the recession has ended.”

Some promising signs of a recovery may be emerging. Foreign investment has increased and, after performing poorly, Brazil’s stock market was one of the best performing in the world in 2016, creating a windfall for the relatively prosperous Brazilians who put money into equities. Mr. Temer is especially bullish, predicting that the economy will grow 3 percent next year. But, the conditions on the streets of cities around Brazil tell a different story, reflecting devilishly complex structural challenges as millions of Brazilians fall into poverty.

Given this scenario, the Brazilian States are facing crippling strikes by public employees over unpaid or inadequate salaries. In the State of Espírito Santo, in Southeast Brazil, a police strike last month produced an anarchic week marked by looting and a surge in homicides.

(Adapted from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/03/world/americas)

According to the text, the austerity measures are:

Faça seu login GRÁTIS

Minhas Estatísticas Completas

Estude o conteúdo com a Duda

Estude com a Duda

Selecione um conteúdo para aprender mais: