Questões de Inglês - Reading/Writing - Dictionary entry

The literary principle according to which the writing and criticism of poetry and drama were to be guided by rules and precedents derived from the best ancient Greek and Roman authors; a codified form of classicism that dominated French literature in the 17th and 18th centuries, with a significant influence on English writing, especially from c.1660 to c.1780. In a more general sense, often employed in contrast with romanticism, the term has also been used to describe the characteristic world-view or value-system of this “Age of Reason”, denoting a preference for rationality, clarity, restraint, order, and decorum, and for general truths rather than particular insights.

(Chris Baldick. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, 2001.)

O termo literário a que o texto se refere é o

A palavra “cringe” viralizou nas redes sociais no Brasil em 2021. Observe sua definição, em português, apontada pelo “Dicionário Informal” on-line:

Vergonha alheia;

Exemplo de uso da palavra cringe:

A cena que presenciamos ontem foi muito cringe.

É cada situação cringe que presenciamos.

Não consigo nem ver, de tão cringe.

Veja, agora, a definição da mesma palavra pelo “Cambridge Dictionary”, também em versão on-line:

to suddenly move away from someone or

something because you are frightened

to feel very embarrassed:

• I cringed at the sight of my dad dancing.

(Disponível em: https://www.dicionarioinformal.com.br/diferenca-entre/crin ge/inglês/; https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/cringe. Acessado em 05/07/2021.)

Com base nessas duas definições, pode-se dizer que, em português, a palavra “cringe”

Read the definitions of the words ideal, idle and idol:

[…]

Idle means something is not in use, empty or doing

nothing.

[…]

Idol is a noun. It means an object that represents a

deity. It is also used to say that you excessively admire

someone.

[…]

Ideal means something that is in its perfection or

something that is most suitable.

[…]

(Available in: https://freevideolectures.com/course/3464/ englsh-grammar/10. Accessed on: January 27th, 2020.)

Complete the sentences below with ideal(s), idle(s) or idol(s):

I - You may use this room, it is _______ for the next six weeks.

II - People normally worship their ________ as gods.

III - Keep calm and answer cordially are the _________ things to do when someone hurts you.

IV - We are justsitting ________ because we don’t have anything to do.

V - For many people, the morning time is ________ to study and learn.

VI - Mom is normally the daughter’s __________.

Check the only alternative that presents all the correct items:

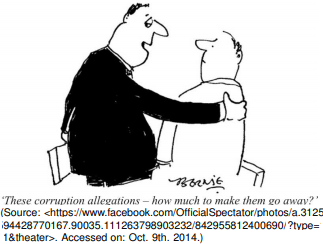

Bribery, the act of promising, giving, receiving, or agreeing to receive money or some other item of value with the corrupt aim of influencing a public official in the discharge of his official duties. When money has been offered or promised in exchange for a corrupt act, the official involved need not actually accomplish that act for the offense of bribery to be complete.

Although bribery originally involved interference with judges, its definition has since been expanded to include actions by all sorts of government officials, from the local to the national level, and to cover all public employees. Special provisions also have been enacted in various jurisdictions to punish the bribing of voters, jurors, witnesses, and other lay participants in official proceedings. Some codes also penalize bribery in designated classes of private or commercial transactions.

(Adapted from: BRIBERY. In: Britannica Online. Enciclopaedia Britannica, 2014. Web, 2014. Source: . Accessed on: Oct. 9th. 2014.)

According to the definition of “bribery” in encyclopedic entry, choose the correct alternative.

Based on the text below, answer question

How New Words Are Created

Below we can find the description of five different processes that have led to the creation of new words in the English language.

(I)

Many of the new words added to the ever-growing lexicon of the English language are Just created out of the blue, and often have little or no etymological pedigree. A good example is the word dog, etymologically unrelated to any other known word, which, in the late Middle Ages, suddenly and mysteriously displaced the Old English word hound (or hund) which had served for centuries.

(II)

Some words arise simply as shortened forms of longer words (exam, gym, lab, bus, vet, phone and burger are some obvious and well- used examples). Perhaps less obvious is the derivation of words like goodbye (a shortening of God-be-with-you) and hello (a shortened form of the Old English for “whole be thou”).

(III)

Like many languages, English allows the formation of words by joining together shorter words (e.g. airport, seashore, fireplace, etc.). The concatenation of words in English may even allow for different meanings depending on the order of combination (e.g. houseboat/boathouse, casebook/bookcase, etc).

(IV)

The drift of word meanings over time often arises, often but not always due to catachresis. By some estimates, over half of all words adopted into English from Latin have changed their meaning in some way over time, often drastically. For example, smart originally meant sharp, cutting or painful; A more modern example is the changing meaning of gay from merry to homosexual (and, in some circles in more recent vears, to stupid or bad).

(V)

New words may arise due to mishearings or misrenderings. According to the “Oxford English Dictionary”, there are at least 350 words in English dictionaries (most of them thankfully quite obscure) that owe their existence purely to typos or other misrenderings (e.g. shamefaced from the original shamefast, penthouse from pentice, sweetheart from sweetard, buttonhole from button-hold, etc).

(Adapted from http://www. thehistoryofenglish.com/issues new.html)

The following headings have been removed from the text and replaced by (I), (II), (III), (IV) and (V).

Choose the alternative which presents them in the correct order.

1 - Change in the Meaning of Existing Words

2 - Creation from Scratch

3 - Fusion or Compounding Existing Words

4 - Truncation or Clipping

5 - Errors

Text

[1] Apart from being about murder,

suicide, torture, fear and madness, horror

stories are also concerned with ghosts,

vampires, succubi, incubi, poltergeists,

[5] demonic pacts, diabolic possession and

exorcism, witchcraft, spiritualism, voodoo,

lycanthropy and the macabre, plus such

occult or quasi occult practices as

telekinesis and hylomancy. Some horror

[10] stories are serio-comic or comic-

grotesque, but none the less alarming or

frightening for that.

From late in the 18th c. until the

present day – in short, for some two

[15] hundred years – the horror story (which is

perhaps a mode rather than an identifiable

genre) in its many and various forms has

been a diachronic feature of British and

American literature and is of considerable

[20] importance in literary history, especially in

the evolution of the short story. It is also

important because of its connections with

the Gothic novel and with a multitude of

fiction associated with tales of mystery,

[25] suspense, terror and the supernatural,

with the ghost story and the thriller and

with numerous stories in the 19th and

20th c. in which crime is a central theme.

The horror story is part of a long

[30] process by which people have tried to

come to terms with and find adequate

descriptions and symbols for deeply

rooted, primitive and powerful forces,

energies and fears which are related to

[35] death, afterlife, punishment, darkness,

evil, violence and destruction.

Writers have long been aware of the

magnetic attraction of the horrific and

have seen how to exploit or appeal to

[40] particular inclinations and appetites. It

was the poets and artists of the late

medieval period who figured out and

expressed some of the innermost fears

and some of the ultimate horrors (real and

[45] imaginary) of human consciousness. Fear

created horrors enough and the

eschatological order was never far from

people‟s minds. Poets dwelt on and

amplified the ubi sunt motif and artists

[50] depicted the spectre of death in paint,

through sculpture and by means of

woodcut. The most potent and frightening

image of all was that of hell: the abode of

eternal loss, pain and damnation. There

[55] were numerous "visions" of hell in

literature.

Gradually, imperceptibly, during the

16th c. hell was "moved‟ from its

traditional site in the center of the earth.

[60] It came to be located in the mind; it was a

part of a state of consciousness. This was

the beginning of the growth of the idea of

a subjective, inner hell, a psychological

hell; a personal and individual source of

[65] horror and terror, such as the chaos of a

disturbed and tormented mind, the

pandaemonium of psychopathic

conditions, rather than the abode of lux

atra and everlasting pain with its definite

[70] location in a measurable cosmological

system.

The horror stories of the late 16th

and early 17th c. (like the ghost stories)

are provided for us by the playwrights.

[75] The Elizabethan and Jacobean tragedians

were deeply interested in evil, crime,

murder, suicide and violence. They were

also very interested in states of extreme

suffering: pain, fear and madness. They

[80] found new modes, new metaphors and

images, for presenting the horrific and in

doing so they created simulacra of hell.

One might cite perhaps a thousand or

more instances from plays in the period c.

[85] 1580 to c. 1642 in which hell is an all-

purpose, variable and diachronic image of

horror whether as a place of punishment

or as a state of mind and spirit. Horrific

action on stage was commonplace in the

[90] tragedy and revenge tragedy of the

period. The satiety which Macbeth claimed

to have experienced when he said: “I have

supp‟d full of horrors;/ Direness, familiar

to my slaughterous thoughts, /Cannot

[95] once start me…” was representative of it.

During the 18th c. (as during the

19th ), in orthodox doctrine taught by

various „churches‟ and sects, hell remained

a place of eternal fire and punishment and

[100] the abode of the Devil. For the most part

writers of the Romantic period and

thereafter did not re-create it as a

visitable place. However, artists were

drawn to “illustrate” earlier conceptions of

[105] hell. William Blake did 102 engravings for

Dante‟s Inferno. John Martin illustrated

Paradise Lost and Gustave Doré applied

himself to Dante and Milton. The actual

hells of the 18th and 19th c. were the

[110] gaols, the madhouses, the slums and

bedlams and those lanes and alleys where

vice, squalor, depravity and unspeakable

misery created a social and moral chaos:

terrestrial counterparts to the horrors of

[115] Dante‟s Circles.

Gothic influence traveled to America

and affected writers such as Edgar Allan

Poe, whose tales are short, intense,

sensational and have the power to inspire

[120] horror and terror. He depicts extremes of

fear and insanity and, through the

operations of evil, gives us glimpses of

hell.

Poe‟s long-term influence was

[125] immeasurable (and in the case of some

writers not altogether for their good), and

one can detect it persisting through the

19th c.; in, for example the French

symbolistes (Baudelaire published

[130] translations of his tales in 1856 and

1857), in such British writers as Rossetti,

Swinburne, Dowson and R. L. Stevenson,

and in such Americans as Ambrose Bierce,

Hart Crane and H.P. Lovecraft.

[135] Towards the end of the 19th c. a

number of British and American writers

were experimenting with different modes

of horror story, and this was at a time

when there had been a steadily growing

[140] interest in the occult, in supernatural

agencies, in psychic phenomena, in

psychotherapy, in extreme psychological

states and also in spiritualism.

The enormous increase in science

[145] fiction since the 1950s has diversified

horror fiction even more than might at

first be supposed. New maps of hell have

been drawn and are being drawn; new

dimensions of the horrific exposed and

[150] explored; new simulacra and exempla

created. Fear, pain, suffering, guilt and

madness (what has already been touched

on in miscellaneous „hells‟) remain

powerful and emotive elements in horror

[155] stories. In a chaotic world, which many

see to be on a disaster course, through

the cracks, „the faults in reality‟, we and

our writers catch other vertiginous

glimpses of „chaos and old night‟,

[160] fissiparating images of death and

destruction.

From: CUDDON, J. A. The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory. London: Penguin, 1999.

Among the many writers influenced by Edgar Allan Poe, the text mentions

Faça seu login GRÁTIS

Minhas Estatísticas Completas

Estude o conteúdo com a Duda

Estude com a Duda

Selecione um conteúdo para aprender mais: